Now Available in paperback, hardcover, eBook, and (soon) audiobook!

Tag: Wit

The Wait Is Almost Over: The Ways to Wit Comes Out This Weekend!

Mark it on your calendar!

Too Much, Twain

It would be disenchanting, if, at a magic show, between each trick, the magician asked if you had yet accepted Jesus Christ as your personal savior. Comedy shows with regular intermissions for the discussion of politics, an evening out with a recent love interest that is persistently punctuated with fond talk of past lovers and chronic bowel obstruction—both things that might take us out of the mood. A phenomenon equally represented in Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

Twain is indubitably a master rhetorician and humorist, and he is at his best when knows this. His rhetorical sleights of hand, riotous turns of phrase, and Romantic depictions of sylvan scenes enchant, enliven, and enrapture. In A Connecticut Yankee, however, Twain achieves high marks in poor form by reminding us that, should a moralist pamphleteer want to masquerade as a fiction writer, he should, at least, do it subtly, as the opposite usually leaves one feeling sinful, humorless, and limp.

There seems to be something of a formula as regards the abovementioned fun-to-guilt ratio. Let us briefly revisit our abovementioned reverent magician. He has about an hour to create insecurity in adults’ intellects and instill in children a reason to live. Religion can perform both of these feats. Even the most pious of deacons known to nod off. Perhaps, however, instead of suggesting his audience follow the path to peace and understanding between each trick, he could just open and end with a powerful, tangential quip about our Lord and Savior—people do worse consistently.

Twain might have employed this sage advice, during his book-length snoozer on Modernity. After his hundredth mentioning of how he “was afraid the Church” and then again, just a yawn later, during a novel moment about how he “was afraid of a united Church,” he felt it a necessity to redefine redundancy: “[the church] makes a mighty power, the mightiest conceivable, and then when it by and by gets into selfish hands, as it is always bound to do, it means death to human liberty, and paralysis to human thought.”

The like continues ad infinitum. Believe it or not, is this not the same gentleman who, when asked about his tips for good writing, noted “don’t say the old lady screamed. Bring her on and let her scream”? Seems to me that Twain, in this case, decided put on the wig and muumuu himself and grab a bullhorn.

What about our politically concerned comedian? Is it so wrong to be worldly, informed, and possess a desire to help others understand the multitude of historical and political contexts that shape the very foundations of consciousness? Yes. This is called being annoying, and it is illegal.

Just as it is the death knell of comedy to complete each joke by subsequently asking if one has fully realized the weight thereof, it is equally important to assume that an audience can form its own thoughts and opinions. Twain, unfortunately, though a former steamboat captain himself, in A Connecticut Yankee, misses the boat the entirely. Only because I cannot, due to laws and so forth, quote the entirety of the book, provided herein is but one of a thousand of Professor Twain’s Intro to Political Science classes:

The painful thing observable about all this business was, (sic) the alacrity with which this oppressed community had turned their cruel hands against their own class in the interest of the common oppressor. This man and woman seemed to feel that in a quarrel between a person of their own class and his lord, it was the natural and proper and rightful thing for that poor devil’s whole caste to side with the master and fight his battle for him, without ever stopping to inquire into the rights and wrongs of the matter…this was depressing…it reminded me of time thirteen centuries away…

Hmm? Excuse me. Was I snoring? Well, this goes on for another two-hundred pages or so, punctuated by what Twain does best: write excellently.

The rule of assuming that your audience also has a sophomoric understanding of political theory applies well here. There are plenty of excellent books as regards the critical examination of political theory, and readers of A Connecticut Yankee are implored read them.

What about our beautiful date from the beginning who just will not stop going on about someone named Devin—a great person with whom an amicable split was made and who still contacts your date regularly, usually at night—and has repeatedly referred to a chronic gastrointestinal disturbance hereditary in its origins? The hard truth of the matter is that Twain’s writing is almost always a 10. It looks good. It swells one with a love for aesthetics. But, then, it speaks, and something happens. The spell is broken. Things go flat.

The Dream Journal of J.D. Solomon Audiobook is Now Available

To anyone who would like me (assisted by the voice of Larry Bull) in his or her ear for six hours, feel the freest to pursue the following link, or search The Dream Journal of J.D. Solomon on Amazon, Audible, or iTunes.

https://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/B0CQTQSZZN/ref=tmm_aud_swatch_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1703636627&sr=8-1

Ta!

J.S.

An Interview with Redbrick’s Rebecca Schleifer

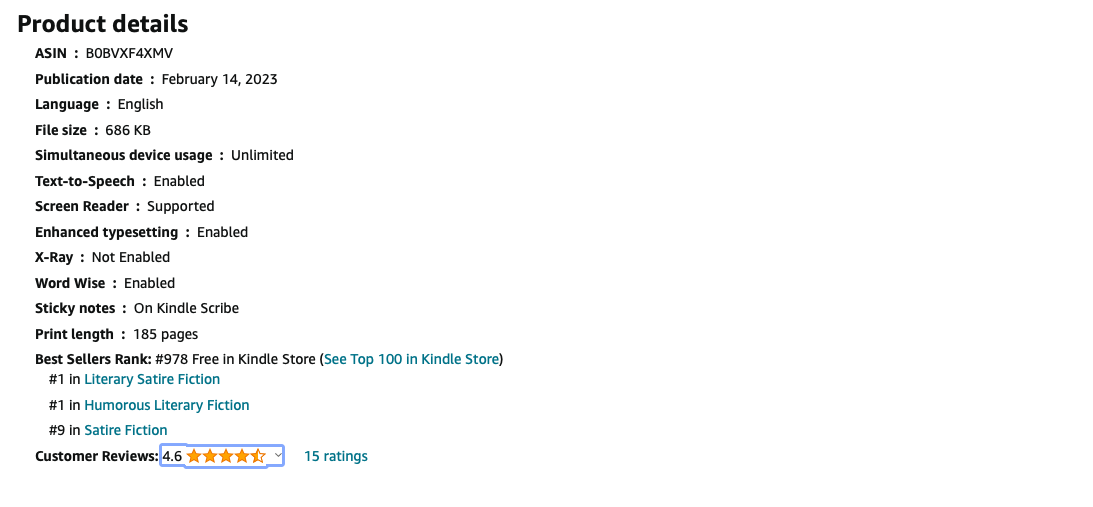

The Dream Journal of J.D. Solomon Reaches #1

Take a Short Story Writing Course with Me

On Looking Funny

Above all, Wodehouse is known for inventing wildly creative, truly unprecedented imagery. How does one even introduce a literary feat of such electricity as the Wodehousian image? Novelist Tom Sharpe was getting the fork pretty close to the socket in Plum, a BBC documentary on Wodehouse, when he said that “you can never write a simile in a comic novel without being aware that it’s been done better…I mean, Wodehouse more or less killed them.”

Aside from an otherworldly writing routine and an exceedingly powerful imagination, Wodehouse had a masterful command of what has been defined as The Four Master Tropes. These Master Tropes have been deemed as playing the central role in the organization of entire systems of thought and therefore much of the literary sense. They are metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony. And, the long and short of the matter is that these tropes divide language, and therefore its product, imagery, into two corresponding parts: what is literally said and what is meant. For the purposes of imagery, we shall endeavor upon three of these four.

Let us start with the two that you do not know. What are metonymy and synecdoche? Simply, synecdoche is a construction in which the writer creates an image that substitutes a part for a whole or whole for a part. This can be understood through common cliches, such as when we call a smart person a “brain,” or a substitute on the football field “fresh legs.” For metonymy, perhaps it is best to refer directly to Wodehouse.

In Young Men in Spats, Wodehouse begins each story as a retrospective yarn. The book begins with “It was the hour of the morning snifter, and a little group of Eggs and Beans and Crumpets had assembled in the smoking room of the Drones Club to do a bit of inhaling.” Whereupon a “glassy-eyed silence…was broken by one of the Crumpets…then a Bean spoke…” then, an “Egg wistfully” sighed. In his short story “The Smile that Wins,” from the collection Mulliner Nights, Wodehouse employs the same tactic, referring to the patrons “in the bar-parlor of the Angler’s Rest” this time not as each element of the full English Breakfast, rather as the adult beverage of his choice. The conversation plays out with this general sentiment: “…said a Pint of Stout, vehemently…insisted a Whisky Sour…demanded a Mild and Bitter.” This is metonymy: a kind of substitution of the name of an attribute or an adjunct for the name of the thing meant.

Needless to say, Eggs, Beans, and Crumpets do not allude only to a full English breakfast—the Pint of Stout, Whisky Sour, and Mild and Bitter not only to poison picked; the discrete elements of the ample breakfast and sundry beverages are the literal image, but the implied association is the appearance of someone, or “type” of person, who might likely enjoy that element of breakfast or that breed of tipple, and, in this way, embody what the each element of food or drink might represent—and perhaps even look like it. And that’s dashed close to anthropomorphism.

In Leave it to Psmith, Psmith’s use of this tactic, whenever describing an event to which he endeavored to bring great weight, was frequent. The husband after being frustrated by a controlling wife: “…a deep masculine silence fell.” A perfectly lazy, midsummer’s dream of an afternoon on the estate: “Blandings Castle dozed in the midsummer heat…” and, as a magnanimous king, “Silence reigned.” Then, at night, “the smooth terrace slept under the stars,” during which the burglary of Lady Constance’s pearl necklace was taking place. Having hid the necklace in a flowerpot to be later retrieved in safety, Eve, the heroine of this novel, now looks upon a flowerpot bereft of that same necklace, and “the flower-pot seemed the leer up at her in mockery.”

At the risk of patronizing readers, I shall now note that similes are a sub-species of metaphor. Similes make implicit comparisons by designating the language of something to something else and use words like, as if, and as though; and one may achieve the same effect through submerged similes, which omit these words through originally fashioned comparative language. And the complete substitution of a word, image, or idea for another, based on an implied resemblance or analogy, is a metaphor.

Metaphors can help one see the unseeable, speak with the unknowable, and make sense of pure shadow. Unlike its cousin, the pun, metaphor is neither an immediate plea to reason nor a result of calculation; metaphor takes counsel from the eternal architypes, summoning the intuition to experience a genuine likeness as if by intravenous. These express comparisons aid one to see everything as a reminder of something else and how the particular characterizes the universal. Indeed, like dreams, metaphors leave impressions of truths that awake the unconscious in a subtly profound way. And, through the employment of surprising juxtapositions of hitherto seemingly unrelated things, the metaphor and the joke have always been firm psychological friends.

As a fact, each and every time one encounters any of Wodehouse’s hundreds of catalysts for comparison, which occur on nearly every page, one witnesses an image blowing out the other side that tests the limits of one’s VO2 Max. One could analyze the Wodehousian Image to death, but this method of analysis on the humorous image, though aboveboard enough, often lobs something of a wet sock into the proceedings. Too much theory to the imagination is like putting one’s lips to the garden hose on a hot day and never taking them off. It kills what was a good thing. Indeed, what is needed is a church of examples, and I, for one, believe it to be better form to take them in and grease up the hassock for genuflection.

Images

Piccadilly Jim : “Mr Pett, on his side, receiving her cold glance squarely between the eyes, felt as if he were being disemboweled by a clumsy amateur.”

“Fate”: “…said Mavis, in a voice which would have left an Eskimo slapping his ribs and calling for the steam-heat…”

Ukridge : “He resembled a minor prophet who has been hit behind the ear with a stuffed eel-skin.”

Ukridge : To hear this dignitary addressed—and in a shout at that—as “old horse” affected me with much the same sense of imminent chaos as would afflict a devout young curate if he saw his bishop slapped on the back.

“Bill The Bloodhound”: If you would have asked him (sic) he would have said that he was a Scotch business man. As a matter of fact, he looked far more like a motor-car coming through a haystack.

“Bill The Bloodhound”: That is to say, he felt like a cat which has strayed into a strange, hostile back-yard.

Leave It to Psmith : “drooping like a wet sock, as was his habit when he had nothing to prop his spine against…”

Joy in the Morning : “She came leaping towards me, like Lady Macbeth coming to get first-hand news from the guest room.”

The Luck of the Bodkins : “Reggie looked like a member of the Black Hand trying to plot assassinations while hampered by a painful gumboil.”

Jeeves in the Offing : “When she spoke, it was with the mildness of a cushat dove addressing another cushat dove from whom it was hoping to borrow money.

“Jeeves and the Impending Doom”: The Right Hon. was a tubby little chap who looked as if he had been poured into his clothes and had forgotten to say ‘When!’

Which Home Do You Choose?

Of satire, there are essentially three forms: Horatian, Juvenalian, and Menippean, invented by Horace, Juvenal, and Menippus, respectively. Each one has a different position towards critique. As I understand it, Horatian satire is akin to gently correcting the behavior of a cherished group of friends by kindly suggesting refinement through warm-hearted raillery. Juvenalian is reserved for when one is having a particularly bad day and interested in a full-frontal knuckle-up with the perceived object responsible for that day’s downward trajectory, often people or institutions. And Menippean is something a bit more abstract, something like inviting those with distasteful ideas and mental attitudes into one’s home and speaking with them about those same ideas and mental attitudes that one finds to be ready for the trash can. Then, without attributing this garbage to them directly, one chooses instead to soften things up a trifle by conveying information through analogy, metaphor, or allegory. In this form, extraordinary settings and narrative abstraction are quite common.

Unlike other forms of humor that rely on generally unbiased observations of human behavior and its foibles, satire operates by placing its selected subject matter under a certain scorn, derision, or ridicule, with the hope that, by doing so, a shock of recognition will jolt through the reader that renders one repulsed by the hitherto uncontemplated vice or folly and in desire of dispossession at the personal or societal level. And a particularly successful satire will have convinced its reader that all will benefit from the banishment of the iniquity exposed and denounced therein.

And, if this reads as at all religious in temperament to you, you are neither imagining things nor gaslighting yourself, for satire requires a special something promised by the divine: judgement.

Satire exists exactly because of its element of judgement, which, channeled through the satirist’s belief system, originates in the satirist’s idea of a more perfect world. The perceived negative elements of personality, philosophy, or society to be receiving the axe are juxtaposed against the satirist’s ideal conceptions thereof, which are championed in a way that should convince the reader of the superiority of those ideals. But a rusty broadsword to the thorax, though diplomatic, won’t quite do here. While satire is, without a doubt, an attack, its vanguard lead neither with lash out nor lambast—seldomly effective routes—rather with humorous irony. A spoonful of sugar makes the satire go down roughshod, and its recuperative effects should eschew the taste of destruction as much as possible, in favor of a constructive relish.

Evelyn Waugh’s 1932 novel, Black Mischief, provides a piercing example of satire anent the theme of birth control. In the Empire of Azania, an advertisement for birth control is placarded on the city wall. And a curious case ensues:

It portrayed two contrasted scenes. On one side a native hut of hideous squalor, overrun with children of every age, suffering from every physical incapacity—crippled, deformed, blind, spotted and insane; the father prematurely aged with paternity squatted by an empty cook-pot; through the door could be seen his wife, withered and bowed with child-bearing, desperately hoeing at their inadequate crop. On the other side a bright parlour furnished with chairs and table; the mother, young and beautiful, sat at her ease eating a huge slice of raw meat; her husband smoked a long Arab hubble-bubble (still a caste mark of leisure throughout the land), while a single healthy child sat between them reading a newspaper. Inset between the two pictures was a detailed drawing of some up-to-date contraceptive apparatus and the words in Sakuyu: WHICH HOME DO YOU CHOOSE?

Interest in the pictures was unbounded; all over the island woolly heads were nodding, black hands pointing, tongues clicking against filed teeth in unsyntactical dialects. Nowhere was there any doubt about the meaning of the beautiful new pictures.

See: on right hand: there is rich man: smoke pipe like big chief: but his wife she no good; sit eating meat: and rich man no good: he only one son.

See: on left hand: poor man: not much to eat: but his wife she very good, work hard in field: man he good too: eleven children: one very mad, very holy. And in the middle: Emperor’s juju. Make you like that good man with eleven children.

As in the case of Modernity, I’m likewise undecided.

What’s the Pointe?

There is a word far more favored on the eastern side of the Atlantic called pointe, which comes from French, which ultimately hails from the Latin punctus, whose infinitive form means “to pick” or “to punch.” Aside from being impossible for the American mouth to pronounce, this word carries the general translation of punchline.

Most English-speaking bipeds know through standup comedy what a punchline is: naptime. Of course, no one with a sense of humor watches standup comedy: a population of former third-shift fast-food managers and recent diversity hires creating a considerable racket about genitalia. A more successful look at this idea, then, would be through the writings of a few considerable Wits who are well known for a most sharp sauce.

Just as in the idea of a punchline, one’s image or notion should always be strongest at the end of one’s sentence, paragraph, scene, or chapter. Let us first consider the renowned essayist, fiction-writer, and rhetorician William Taft—excuse me—G.K. Chesterton and how, in his 1908 essay Woman, he makes his point by putting the strongest image at the end of very nice pieces of sentence-length rhetoric, the likes of which I imagine he wrote in a tub:

He knows it would be cheaper if a number of us ate at the same time, so as to use the same table. So it would. It would also be cheaper if a number of us slept at different times, so as to use the same pair of trousers.

The parallelism of these two sentences is undeniably satisfying. Furthermore, the repetition of concrete nouns, table and trousers, respectively, at the end of each sentence, hammers home the loose logic of his statements in such a way that heads nod strongly and headlines read “Chesterton by a mile!”

Sir Kenneth Clark, popularly known for his documentary Civilisation, wrote a book called, well, Civilisation. In the book, Clark admits that he found it a trifle contrived to write a book about the documentary that he made, covering all the same topics in a fashion that seemed now a bit stilted. Nevertheless, Clark’s delightful writing style leaves the reader glad that he did. Here, Clark, amongst a few rhetorical schemes operating in accordance with each other, renders the end of each phrase and sentence with a powerful word about the things that he finds less than desirable:

I believe that order is better than chaos, creation better than destruction. I prefer gentleness to violence, forgiveness to vendetta. On the whole I think that knowledge is preferable to ignorance, and I am sure that human sympathy is more valuable than ideology.

The King of Sting, Mark Twain, who was also not entirely unaccustomed to providing readers with his various opinions, is seen here sending over a stiff one on the state of women in 1870s Salt Lake, Utah:

With the gushing self-sufficiency of youth I was feverish to plunge in headlong and achieve a great reform here—until I saw the Mormon women.

Why waste perfectly good heartbeats searching for similes with endings powerful enough to leave Isaac smiling and saying “check this out, dad,” as a heavily breathing Abraham comes around the corner with the rope and kitchen knife, when P.G. Wodehouse had walked the Earth for almost a hundred years? Pick any page in Piccadilly Jim and the following can be found:

Mr Pett, on his side, receiving her cold glance squarely between the eyes, felt as if he were being disemboweled by a clumsy amateur.

He had contrived to create about himself such a defensive atmosphere of non-existence that now that he re-entered the conversation it was as if a corpse had popped out of its tomb like a jack-in-the-box.

Ending those similes in “amateur” and “jack-in-the-box” is a work of such fine distinction that one gets the feeling that Wodehouse was ordered from God to carry out the task, saying, “I’m sad and unpredictable today. I need a laugh. What do you got?”

Even the obscure writer, Joshua Smith, in his 2021 comedy novel The Dream Journal of J.D. Solomon, was able to crack a few off successfully. In the opening chapter of the book, the book’s main character, J.D. Solomon, attempts to get out of a tight spot on a public train by pretending to answer a phone call with his wallet:

Therefore, as I had never owned a cellular phone, I disengaged eye-contact with the gentleman and adjusted proximity by way of clever wandering betwixt cabins, feigning a phone call by way of open bifold wallet to ear.

Is it poor form to reference one’s own book in an essay? That is up for debate. But, you see my point.

The theologically inclined amongst us believe the number three to hold divine power, as in the Trinity and the bacon, egg, and cheese sandwich, whilst the Darwinists remind us that our love of threes has more to do with being clubbed on the head by one’s neighbor and generally made soup of. Regardless of whether you believe in The Witching Hour or confine your study to this Earth of ours, one may enjoy the spoils of this comfortable certainty thrice over through the act of careful composition. And, whether you deal in triangles, trilogies, or tricycles its best to do it in threes.

This is not unlike good writing. There is a concept in writing called Rearrangement. The general gist of rearrangement is to place the emphasis of a sentence where it is to elicit the greatest response from the reader. The least emphatic part of a sentence is the middle, the second most emphatic is the first spot, and most emphatic is stalwart number three. Known for having something of a grasp on rhetoric, Shakespeare committed rearrangement (and tricolon) when he wrote: We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.